Male Brains Shrink Faster Than Female Brains, Study Finds

A comprehensive new study suggests that male brains may age faster than female brains — at least when it comes to volume loss. The findings add fresh nuance to a long-standing question in neuroscience: how does biological sex affect brain aging?

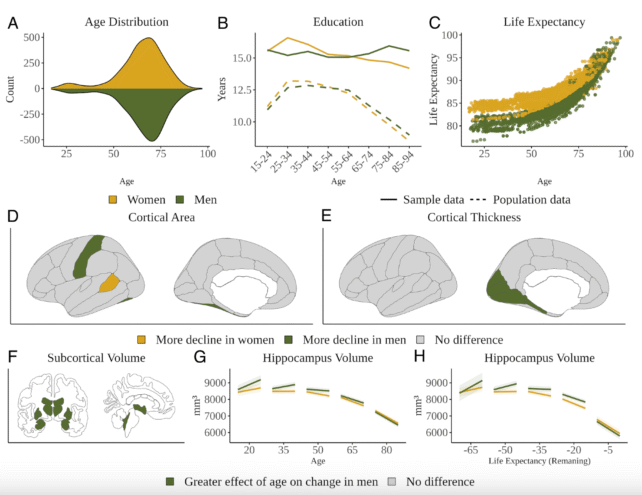

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the study analyzed more than 12,000 brain scans from 4,726 individuals aged 17 to 95. All participants were cognitively healthy and had undergone at least two brain MRIs over time, offering a rare longitudinal look into the aging human brain.

The Shrinking Brain: A Gender Divide

As the human brain ages, it naturally shrinks — a process that accelerates in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. But while women are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, the biological reasons behind this disparity remain murky.

Surprisingly, this new research shows that male brains actually shrink faster than female brains in several key regions — including across large areas of the cortex, the brain’s outer layer responsible for higher-order functions such as perception, language, and memory.

“If women’s brains declined more, that could have helped explain their higher Alzheimer’s prevalence,” said co-author Anne Ravndal, a neuroscientist at the University of Oslo, in a statement to Nature. “But that’s not what we’re seeing.”

A Global Collaboration, A Massive Dataset

The international team compiled one of the largest brain imaging datasets to date, spanning nearly eight decades of life. Importantly, the study accounted for baseline sex differences in brain size — male brains are typically larger in volume — and focused on relative changes over time.

What emerged were “modest yet systematic” differences in how the brain loses gray and white matter across the sexes:

- Men showed more volume loss across multiple cortical and subcortical regions.

- Women, by contrast, retained more cortical thickness and exhibited fewer declines in overall brain regions.

Interestingly, there was no significant sex-based difference in the rate of volume change in the hippocampus — the brain’s memory center and a region closely associated with dementia — at least not until very late in life.

Interpreting the Findings With Caution

Despite the headline-making results, researchers urge caution in interpretation. The study reveals correlation, not causation, and does not fully explain why women, despite showing slower brain shrinkage, are more prone to Alzheimer’s.

Later-life changes in the hippocampus among women may reflect delayed aging processes, rather than disease risk. When researchers adjusted for life expectancy — women tend to live longer than men — the difference in hippocampal shrinkage began to balance out.

This complicates efforts to link structural decline directly to dementia risk. Ravndal notes that “the picture is far from complete.”

Sex Bias in Neuroscience Still a Barrier

One of the most pressing issues highlighted by the study is the gender imbalance in brain research. A 2023 review found that only 5% of neuroscience and psychiatry studies explicitly considered sex differences.

This persistent bias, experts argue, has serious public health consequences — particularly for women.

“Research on the aging female brain is long overdue,” the review stated, warning that overlooking sex in aging studies places a “disproportionate burden” on female health and skews clinical understanding of diseases like Alzheimer’s.

What Does This Mean for Cognitive Health?

The implications of this research go beyond biological curiosity. Understanding how and why male and female brains age differently could inform more targeted treatments, early diagnostics, and personalized interventions for neurodegenerative conditions.

But for now, experts emphasize the need for more longitudinal research that includes diverse participants and measures not just brain structure, but also function, genetics, lifestyle, and environmental factors.

Until then, the study remains a compelling data point in a larger, unfinished puzzle: how sex shapes the aging brain — and why it matters.