How Scientists Cracked the “Impossible” Black Hole Collision That Challenged Relativity

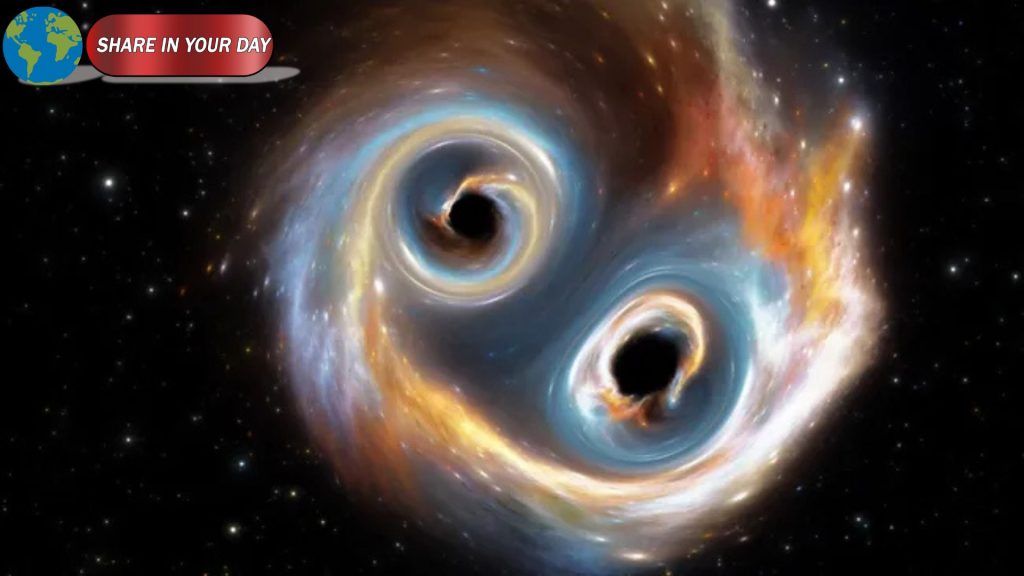

In 2023, detectors recorded a gravitational-wave signal from a pair of black holes merging — but the event left astrophysicists scratching their heads. The black holes, weighing in at roughly 100 and 130 times the mass of the Sun, seemed to defy theoretical expectations. Stars of that size shouldn’t collapse into black holes at all — they were supposed to explode, not leave a remnant. Yet there they were, spinning rapidly, spiraling inward, and merging into a gargantuan final object.

This merger, known as GW231123, occupied a “forbidden” region in black hole theory: the so-called mass gap, roughly between 70 and 140 solar masses. In standard stellar evolution, pair-instability supernovae should tear such massive stars apart entirely — leaving no black hole behind.

Simulating the Unthinkable

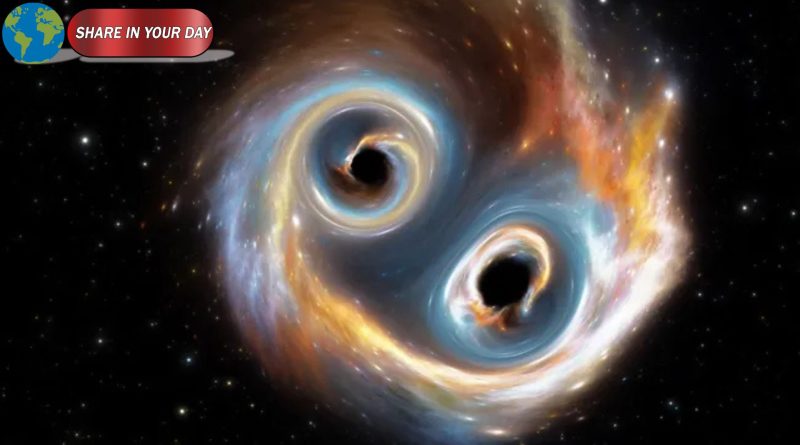

To unravel this mystery, a team led by astrophysicist Ore Gottlieb ran detailed, three-dimensional computational simulations of a rapidly spinning, massive star collapsing. What they found was surprising: magnetic fields inside the star’s accretion disk generated by its fast rotation can drive powerful outflows, ejecting significant portions of the star’s mass into space instead of feeding it into the nascent black hole.

These magnetic outflows limit how much material actually falls into the forming black hole. In extreme cases, up to half of the original mass can be expelled. That reduction in accretion helps the resulting black hole fall squarely into the mass gap — precisely where GW231123’s progenitors appeared to lie.

Spin and Mass Linked

Not only does this mechanism explain the unexpected mass — it also accounts for the black holes’ rapid spin. In the simulations, strong magnetic fields siphon off angular momentum, slowing the black hole’s rotation while pushing away more mass. Weaker fields allow more mass to remain and the black hole to spin more rapidly.

Remarkably, this predicted relationship closely matches what scientists inferred from the gravitational-wave signal of GW231123. One black hole likely formed in an environment with moderate magnetic field strength; the other from a region with weaker magnetism — giving rise to the distinct spins and masses that merged.

Why This Matters for Gravity

Events like GW231123 aren’t just curiosities — they push Einstein’s general relativity to its limits. The extreme curvature of space-time in such massive, spinning mergers gives scientists a rare opportunity to test whether Einstein’s equations still hold in the most intense gravitational environments.

If these “forbidden” black holes are more common than we thought, it could reshape our understanding of how early-generation black holes formed in the universe. Simulations like these suggest that massive, rapidly spinning stars with strong magnetic fields might have seeded many of the black holes we observe today.

Looking Ahead

The next step is observational: as gravitational-wave astronomy improves, scientists will look for more mergers similar to GW231123. If they find a population of black holes in the mass gap whose spin and mass follow the pattern predicted by the simulations, it would strongly support this new model.

Moreover, this discovery opens a new window into black hole formation — not just through colliding black holes, but from single, massive stars influenced by magnetic dynamics. It’s a reminder that even well-established theories sometimes need a tweak, and that astrophysics continues to surprise us