Fighting from Within: An Inside Resistance

Years ago, during a stint in county lockup, I encountered a poem by Dylan Thomas: “Do not go gentle into that good night… Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” I was drawn to its urgency — though at the time, I couldn’t fully grasp what it meant to “rage” from inside the belly of the beast.

Soon, I would learn.

At 25, while held in solitary confinement at the Hudson County Correctional Center in Kearny, New Jersey, I started studying law. I was educated, worldly, had run a business — yet inside a courtroom, I felt lost: the jargon, procedures, and timing were foreign. I asked my lawyers questions — but I didn’t press them. I trusted them. Still, I landed two life sentences: 150 years.

That failure haunts me. Over time I came to realise the system expects submission: sit down, stay quiet, comply. Every misstep — even a misunderstood plea or a lawyer’s error — becomes another chain.

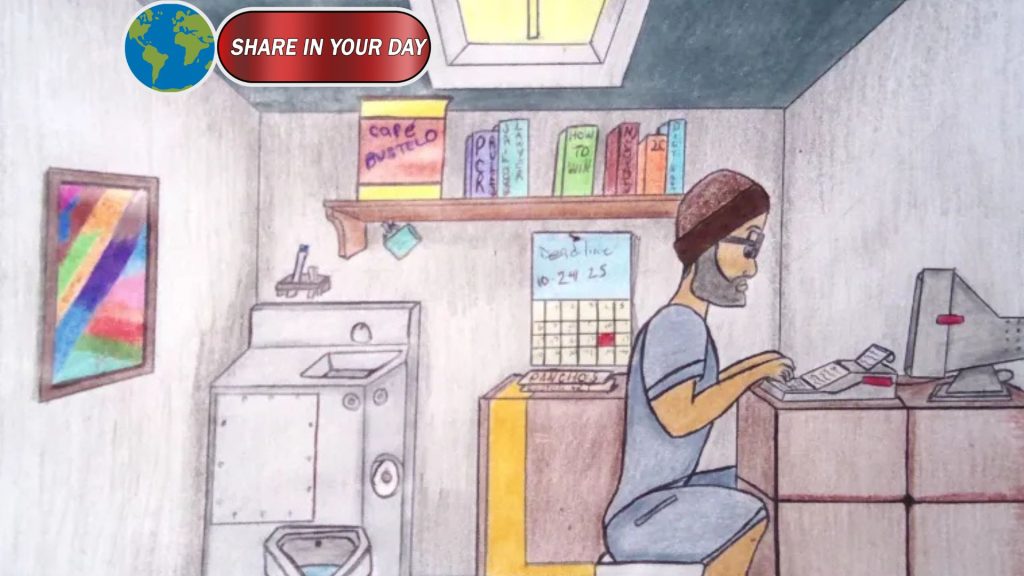

The Law Library: Where Defence Begins

When I arrived at the New Jersey State Prison (NJSP) in 2005, an older inmate told me: “Your job is to stay out of trouble, live, and fight for your life. There are no saviours. Get to the law library and learn.”

So I joined the Inmate Legal Association (ILA), a prisoner-run paralegal group. They trained me in legal research and self-representation. Before long, I was filing motions — for myself and for others.

One early victory was a procedural motion that got a fellow inmate back into court. That win, fragile and fleeting though it was, felt like a trophy.

I even filed a habeas corpus petition challenging my conviction. The court dismissed it — but I appealed. I trusted my research. And I won. Virtually overnight, the victory was overturned — the petition denied. Still, it proved something: we could push back.

Pro Se Litigants — Forced to Represent Themselves

Many of us behind bars must act as our own legal counsel. After initial appointments and early appeals, most cannot afford ongoing representation. We’re left to navigate an intimidating environment alone.

Data backs this up: between 2000 and 2019, U.S. court records show that about 91% of legal challenges filed by prisoners were pro se — meaning filed by inmates themselves.

One of the hardest barriers is access — or lack thereof — to the law library. Prisoners must request passes to visit, but these are limited. Sometimes weeks pass before you get in. Deadlines imposed by courts don’t care. Missing a brief — even with a legitimate excuse like a medical injury — can mean automatic denial.

A Hidden Resistance — Hope, Education, Solidarity

Still, we fight. In dimly lit cells, under flickering lights, we write motions. We grind out research. We teach others how to navigate legal briefs and decode arcane jargon. Some even start informal classes: one inmate at NJSP began teaching the first-ever Spanish-language law class inside the prison.

I myself am working on a pending motion for DNA testing — one that I hope might prove my innocence. Meanwhile, others seek clemency or sentence vacatur. It’s slow. Risky. Often full of denial. But it matters.

Because we do not go gentle into that good night. We rage — against systemic injustice, wrongful convictions, indifferent judges, and a system designed to silence us. When no one else will fight, we fight for ourselves.

Rage, after all, becomes hope in motion