Trump & the Third Term: How the Constitution May Not Be Enough

In recent weeks, the question of whether Donald Trump might seek a third term in the White House has gone from fringe chatter to a matter of serious political concern. As Trump publicly mused about the possibility — and his allies floated strategies around the edges of constitutional rules — the larger question surfaced: even if the Constitution technically bars it, is that barrier still secure?

The proposal — and how it’s being floated

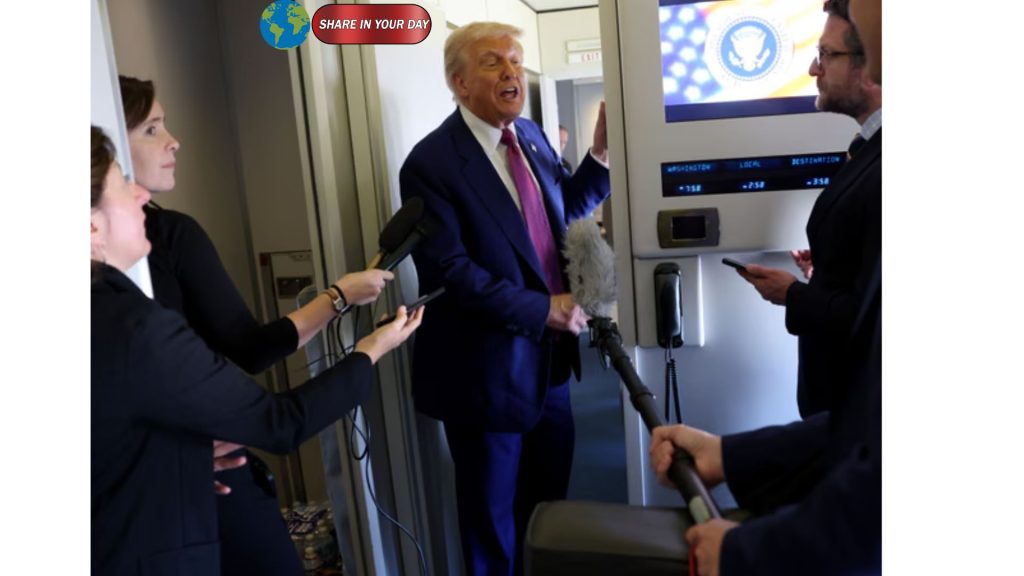

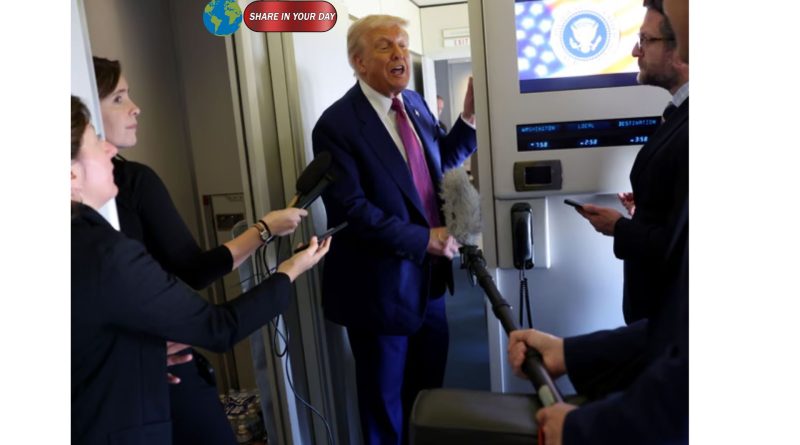

Trump’s provocative remark came soon after his former adviser, Steve Bannon, declared that “Trump is going to be president in ’28,” signalling a plan to claim power beyond the standard two-term limit.

Trump followed up on an official trip by saying, “I would love to do it,” acknowledging the idea while noting he hadn’t fully thought it through.

One hypothetical strategy involves running as his own vice-presidential nominee (he questioned the “cute” alternative of being the VP to someone else), with that person resigning in office to hand the presidency to him — but this too would collide with the 12th Amendment’s restriction on ineligible persons serving as vice-president.

The clear legal barrier — but also the erosion of enforcement

On its face, the 22nd Amendment plainly disallows a person from being elected President more than twice — which would seem to block a third Trump term.

But the piece by columnist Moira Donegan argues that, in the current moment, the constitutional text may not be a dependable safeguard. She points to how the Supreme Court and allied academics have already undermined or interpreted away other constitutional constraints — for example, in cases involving the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause and the dismantling of federal agencies.

Why the constitutional guard-rails are weakening

The Supreme Court now has a majority of justices perceived as friendly to Trump-aligned positions, which shifts the gate-keeping of constitutional interpretation.

Legal scholarship from sympathetic academics is being used to provide cover for expansive executive actions — in effect, to outsource the reinterpretation of constitutional limits.

Because constitutional change relies on enforcement, norms and institutional checks matter. When those are weakened, the written text may become less meaningful. Donegan argues that this makes relying purely on the 22nd Amendment naive.

What to watch moving forward

How the courts respond if a tangible attempt at a third term emerges — whether through candidacy filings, party nominations, or other mechanisms.

Whether Congress, state governments or civil society mobilise ahead of any serious bid, recognising that the law may not be enough alone.

The precedent being set for constitutional interpretation: if restrictions like term-limits are bypassed or undermined, what stops other foundational protections from being next?

Final thought

The conversation about Trump’s possible third term is about more than one man — it underscores a broader risk: when the written Constitution and its amendments remain, but the institutions and traditions that enforce them falter, the protections they promise begin to unravel.

If the rule-book is still the Constitution, the game might already be changing